PostgreSQL 101

PostgreSQL is the finest open source example of the relational database management system (RDBMS) tradition. This means that PostGreSQL is a design-first data store. First you design the schema, and then you enter data that conforms to the definition of that schema.

History of PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL has existed in the current project incarnation since 1995, but its roots

are considerably older. The original project was written at Berkeley in the early 1970s

and called the Interactive Graphics and Retrieval System, or “Ingres” for short. In the

1980s, an improved version was launched post-Ingres—shortened to Postgres. The

project ended at Berkeley proper in 1993 but was picked up again by the open source

community as Postgres95. It was later renamed to PostgreSQL in 1996 to denote its

rather new SQL support and has remained so ever since.

Installation

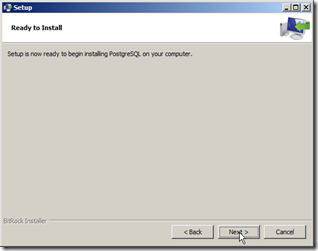

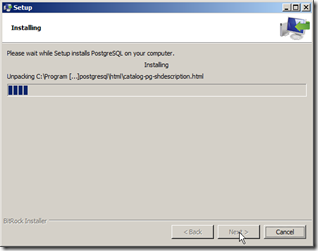

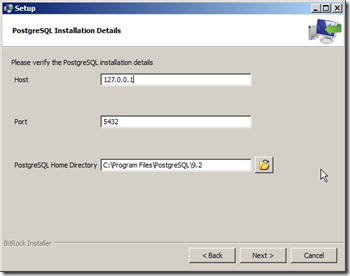

You can download the latest PostgreSQL installer from http://www.postgresql.org/download (In this tutorial I’m using the Windows 64bit installer). Setup is straight-forward. Below are screen-shots of installation steps:

remember the superuser password, you will need it later

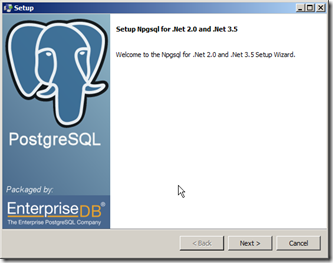

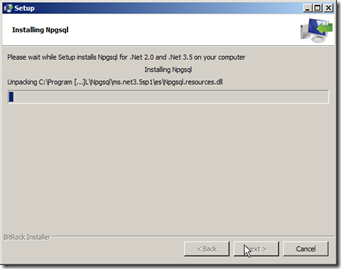

when the PostgreSQL installation finish, you could choose to run Stack Builder to install additional tools. In my case I chose to run Stack builder

choose your recently installed instance

and I choose to install Npgsql database driver (for future .Net development) and phpPgAdmin for administration tasks.

Stack Builder will lunch installation wizards for your chosen tools in sequence

Starting with PostgreSQL

To get started, open pgAdmin III from your start menu. On the left hand side right-click on your server instance and click Connect

enter the password you used in the setup

Once you connected to your server, you can right click on the databases node and click New Database

we going to create a simple database called book with the default settings

to start writing queries, you could open Tools menu, then click Query Tool (or press CTRL + E).

Working with Tables

Creating a table consists of giving it a name and a list of columns with types

and (optional) constraint information. Each table should also nominate a

unique identifier column to pinpoint specific rows. That identifier is called a

PRIMARY KEY. The SQL to create a countries table looks like this:

CREATE TABLE countries (country\_code char(2) PRIMARY KEY,country\_name text UNIQUE);

copy and paste this code in the Query Tool and click

To insert values in our countries table:

INSERT INTO countries (country\_code, country\_name)

VALUES ('us','United States'), ('mx','Mexico'), ('au','Australia'),

('uk','United Kingdom'), ('de','Germany'), ('ll','Loompaland');

To select from our table:

SELECT \* FROM countries;

To delete :

DELETE FROM countries

WHERE country\_code = 'll';

Now, let’s add a cities table. To ensure any inserted country_code also exists in our countries table, we add the REFERENCES keyword. Since the country_code column references another table’s key, it’s known as the foreign key constraint.

CREATE TABLE cities (

name text NOT NULL,

postal\_code varchar(9) CHECK (postal\_code <> ''),

country\_code char(2) REFERENCES countries,

PRIMARY KEY (country\_code, postal\_code)

);

we constrained the name in cities by disallowing NULL values. We constrained postal_code by checking that no values are empty strings (<> means not equal). Furthermore, since a PRIMARY KEY uniquely identifies a row, we created a compound key: country_code + postal_code. Together, they uniquely define a row. now if you try to run this code you will get an error because we violating referential integrity:

INSERT INTO cities

VALUES ('Toronto','M4C1B5','ca');

To update records:

INSERT INTO cities

VALUES ('Portland','87200','us');

UPDATE cities

SET postal\_code = '97205'

WHERE name = 'Portland';

Inner Join

Being a relational database gives PostgreSQL the ability to join tables together when reading them. Joining, in essence, is an operation taking two separate tables and combining them in some way to return a single table. It’s somewhat like shuffling up Scrabble pieces from existing words to make new words. The basic form of a join is the inner join. In the simplest form, you specify two columns (one from each table) to match by, using the ON keyword.

SELECT cities.\*, country\_name

FROM cities INNER JOIN countries

ON cities.country\_code = countries.country\_code;

The join returns a single table, sharing all columns’ values of the cities table plus the matching country_name value from the countries table. We can also join a table like cities that has a compound primary key. To test a compound join, let’s create a new table that stores a list of venues. A venue exists in both a postal code and a specific country. The foreign key must be two columns that reference both cities primary key columns. (MATCH FULL is a constraint that ensures either both values exist or both are NULL.)

CREATE TABLE venues (

venue\_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

name varchar(255),

street\_address text,

type char(7) CHECK ( type in ('public','private') ) DEFAULT 'public',

postal\_code varchar(9),

country\_code char(2),

FOREIGN KEY (country\_code, postal\_code)

REFERENCES cities (country\_code, postal\_code) MATCH FULL

);

This venue_id column is a common primary key setup: automatically incremented integers (1, 2, 3, 4, and so on…). Creating new row will populate this column automatically. We make this identifier using the SERIAL keyword. CHECK keyword check that a column supplied value against a set of predefined values. DEFAULT provide a default value to be inserted in case user supplied nothing.

INSERT INTO venues (name, postal\_code, country\_code)

VALUES ('Crystal Ballroom', '97205', 'us');

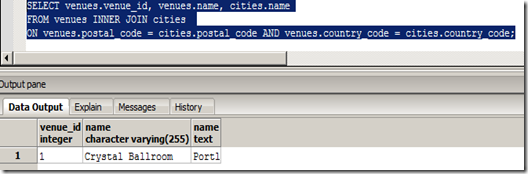

Joining the venues table with the cities table requires both foreign key columns.

SELECT venues.venue\_id, venues.name, cities.name

FROM venues INNER JOIN cities

ON venues.postal\_code = cities.postal\_code AND venues.country\_code = cities.country\_code;

Outer Join

Outer joins are a way of merging two tables when the results of one table must always be returned, whether or not any matching column values exist on the other table. Let’s create a table and populate it for testing this:

CREATE TABLE events (

event\_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

title varchar(255),

starts timestamp,

ends timestamp,

venue\_id integer,

FOREIGN KEY (venue\_id)

REFERENCES venues (venue\_id) MATCH FULL

);

INSERT INTO events (title, starts, ends, venue\_id)

VALUES ('LARP Club', '2012-02-15 17:30:00', '2012-02-15 19:30:00', 1);

INSERT INTO events (title, starts, ends)

VALUES ('April Fools Day', '2012-04-01 00:00:00', '22012-04-01 23:59:00');

INSERT INTO events (title, starts, ends)

VALUES ('Christmas Day', '2012-12-25 00:00:00', '2012-04-01 23:59:00');

Now the results of the following two queries showing you the difference between INNER JOIN and OUTER JOIN.

SELECT events.title, venues.name

FROM events JOIN venues

ON events.venue\_id = venues.venue\_id;

SELECT events.title, venues.name

FROM events LEFT JOIN venues

ON events.venue\_id = venues.venue\_id;

Finally, there’s the FULL JOIN, which is the union of LEFT and RIGHT; you’re guaranteed all values from each table, joined wherever columns match.

Indexes

RDBMSs uses indexes to reducing disk reads and query optimization (among other things). If we select the title of Christmas Day from the events table, the algorithm must scan every row for a match to return. Without an index, each row must be read from disk to know whether a query should return it. An index is a special data structure built to avoid a full table scan when performing a query. PostgreSQL (like any other RDBMS) automatically creates an index on the primary key, where the key is the primary key value and where the value points to a row on disk. Using the UNIQUE keyword is another way to force an index on a table column. PostgreSQL also creates indexes for columns targeted by FOREIGN KEY constraint.

You can explicitly add a hash index using the CREATE INDEX command, where each value must be unique. btree is the suitable data structure for ranges. For more information, refer to online documentation.

CREATE INDEX events\_starts

ON events USING btree (starts);

Aggregate Functions

An aggregate query groups results from several rows by some common criteria. It can be as simple as counting the number of rows in a table or calculating the average of some numerical column. Examples:

SELECT count(title)

FROM events

SELECT min(starts), max(ends)

FROM events

Aggregate functions are useful but limited on their own. If we wanted to count all events at each venue, we could write the following for each venue ID (which is tedious):

SELECT count(\*) FROM events WHERE venue\_id = 1;

SELECT count(\*) FROM events WHERE venue\_id = 2;

SELECT count(\*) FROM events WHERE venue\_id = 3;

SELECT count(\*) FROM events WHERE venue\_id IS NULL;

Grouping

With GROUP BY, you tell Postgres to place the rows into groups and then perform some aggregate function (such as count()) on those groups.

SELECT venue\_id, count(\*)

FROM events

GROUP BY venue\_id;

The GROUP BY condition has its own filter keyword: HAVING. HAVING is like the WHERE clause, except it can filter by aggregate functions (whereas WHERE cannot).

SELECT venue\_id

FROM events

GROUP BY venue\_id

HAVING count(\*) = 1;

You can use GROUP BY without any aggregate functions. If you SELECT one column, you get all unique values.

SELECT venue_id FROM events GROUP BY venue_id;

This kind of grouping is so common that SQL has a shortcut in the DISTINCT keyword.

SELECT DISTINCT venue_id FROM events;

The results of both queries will be identical.

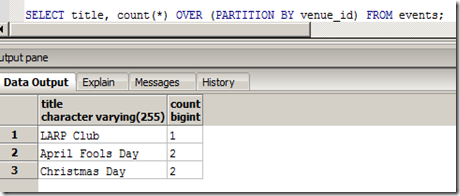

Window Functions

Window functions are similar to GROUP BY queries in that they allow you to run aggregate functions across multiple rows. The difference is that they allow you to use built-in aggregate functions without requiring every single field to be grouped to a single row. If we attempt to select the title column without grouping by it, we can expect an error.

We are counting up the rows by venue_id, and in the case of LARP Club and Wedding, we have two titles for a single venue_id. Postgres doesn’t know which title to display. Whereas a GROUP BY clause will return one record per matching group value, a window function can return a separate record for each row. Window functions return all matches and replicate the results of any aggregate function. It returns the results of an aggregate function OVER a PARTI TI ON of the result set.

Transactions

Transactions ensure that every command of a set is executed. If anything fails along the way, all of the commands are rolled back like they never happened. It’s the all or nothing motto that gives relational databases its consistency capability.

PostgreSQL transactions follow ACID compliance, which stands for Atomic (all ops succeed or none do), Consistent (the data will always be in a good state—no inconsistent states), Isolated (transactions don’t interfere), and Durable (a committed transaction is safe, even after a server crash). Transactions are useful when you’re modifying two tables that you don’t want out of sync.

We can wrap any transaction within a BEGIN TRANSACTION block. To verify atomicity, we’ll kill the transaction with the ROLLBACK command.

Stored Procedures

Every command we’ve seen until now has been declarative (executed on the client side), but you can execute code on the database side also. Example of a stored procedure and how to run it:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION add\_event( title text, starts timestamp,

ends timestamp, venue text, postal varchar(9), country char(2) )

RETURNS boolean AS $$

DECLARE

did\_insert boolean := false;

found\_count integer;

the\_venue\_id integer;

BEGIN

SELECT venue\_id INTO the\_venue\_id

FROM venues v

WHERE v.postal\_code=postal AND v.country\_code=country AND v.name ILIKE venue

LIMIT 1;

IF the\_venue\_id IS NULL THEN

INSERT INTO venues (name, postal\_code, country\_code)

VALUES (venue, postal, country)

RETURNING venue\_id INTO the\_venue\_id;

did\_insert := true;

END IF;

\-- Note: not an “error”, as in some programming languages

RAISE NOTICE 'Venue found %', the\_venue\_id;

INSERT INTO events (title, starts, ends, venue\_id)

VALUES (title, starts, ends, the\_venue\_id);

RETURN did\_insert;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

SELECT add\_event('House Party', '2012-05-03 23:00',

'2012-05-04 02:00', 'Run''s House', '97205', 'us');

Triggers

Triggers automatically fire stored procedures when some event happens, like an insert or update. They allow the database to enforce some required behavior in response to changing data.

Let’s create a function that logs any event changes into logs table. First we create the table

CREATE TABLE logs (

event\_id integer,

old\_title varchar(255),

old\_starts timestamp,

old\_ends timestamp,

logged\_at timestamp DEFAULT current\_timestamp

);

Next, we build a function to insert old data into the log. The OLD variable represents the row about to be changed (NEW represents an incoming row, which we’ll see in action soon enough). Output a notice to the console with the event_id before returning. Then we create our trigger to log changes after any row is updated through this function.

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION log\_event() RETURNS trigger AS $$

DECLARE

BEGIN

INSERT INTO logs (event\_id, old\_title, old\_starts, old\_ends)

VALUES (OLD.event\_id, OLD.title, OLD.starts, OLD.ends);

RAISE NOTICE 'Someone just changed event #%', OLD.event\_id;

RETURN NEW;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

CREATE TRIGGER log\_events

AFTER UPDATE ON events

FOR EACH ROW EXECUTE PROCEDURE log\_event();

To test our trigger let’s update an event and see the trigger output:

and the old event was logged

Views

Views are aliased queries that can be queried by its alias like any other table. Creating a view is as simple as writing a query and prefixing it with CREATE VIEW some_view_name AS. Views are good for opening up complex queried data in a simple way. If you want to add a new column to the view, it will have to come from the underlying table.

CREATE VIEW holidays AS

SELECT event\_id AS holiday\_id, title AS name, starts AS date

FROM events

WHERE title LIKE '%Day%' AND venue\_id IS NULL;

SELECT name, to\_char(date, 'Month DD, YYYY') AS date

FROM holidays

WHERE date <= '2012-04-01';

The RULE system

The rule system (more precisely speaking, the query rewrite rule system) is totally different from stored procedures and triggers. It modifies queries to take rules into consideration, and then passes the modified query to the query planner for planning and execution. More information can be found here. Example of changing query to allow updating our holidays view:

CREATE RULE update\_holidays AS ON UPDATE TO holidays DO INSTEAD

UPDATE events

SET title = NEW.name,

starts = NEW.date

WHERE title = OLD.name;

UPDATE holidays SET date = '6/25/2013' where name = 'Christmas Day';

Crosstab

crosstab(text source\_sql, text category\_sql) takes two queries to pivot results on one of them on the results of the other.

-

source_sql is a SQL statement that produces the source set of data. This statement must return one row_name column, one category column, and one value column. It may also have one or more “extra” columns. The row_name column must be first. The category and value columns must be the last two columns, in that order.

-

category_sql is a SQL statement that produces the set of categories. This statement must return only one column. It must produce at least one row, or an error will be generated. Also, it must not produce duplicate values, or an error will be generated.

If this is the first time you use something from the tablefunc module, you may need to install it to your database by running CREATE EXTENSION tablefunc;

create table sales(year int, month int, qty int);

insert into sales values(2007, 1, 1000);

insert into sales values(2007, 2, 1500);

insert into sales values(2007, 7, 500);

insert into sales values(2007, 11, 1500);

insert into sales values(2007, 12, 2000);

insert into sales values(2008, 1, 1000);

select \* from crosstab(

'select year, month, qty from sales order by 1',

'select m from generate\_series(1,12) m'

) as (

year int,

"Jan" int,

"Feb" int,

"Mar" int,

"Apr" int,

"May" int,

"Jun" int,

"Jul" int,

"Aug" int,

"Sep" int,

"Oct" int,

"Nov" int,

"Dec" int

);

Full-Text Search

Full-text search enables the user to search text columns with parts of the column value, not the exact value like in regular queries.

-

LIKE and ILIKE : LIKE and ILIKE (case-insensitive LIKE) are the simplest forms of text search. LIKE compares column values against a given pattern string. The % and _ characters are wildcards. % matches any number of any characters, and _ matches exactly one character.

-

SELECT title FROM movies WHERE title ILIKE ‘stardust%’;

- will return movies with titles like : “Stardust” or “Stardust Memories”

-

-

Regex : You could write the WHERE part of your queries against text columns in regular expressions. A regular expression match is led by the ~ operator, with the

optional ! (meaning, not matching) and * (meaning case insensitive). So, to count all movies that do not begin with the, the following case-insensitive query will work. The characters inside the string are the regular expression.- SELECT COUNT(*) FROM movies WHERE title !~* ‘^the.*’;

-

Bride of Levenshtein : Levenshtein is a string comparison algorithm that compares how similar two strings are by how many steps are required to change one string into another. Each replaced, missing, or added character counts as a step (Changes in case cost a point too). The distance is the total number of steps away. levenshtein() function is provided by the fuzzystrmatch contrib package.The following query return 3 because we need to replace 2 characters and and add 1 character to make bat into fads.

- SELECT levenshtein(‘bat’, ‘fads’);

-

Trigram : A trigram is a group of three consecutive characters taken from a string. The pg_trgm contrib module breaks a string into as many trigrams as it can. Finding a matching string is as simple as counting the number of matching trigrams. The strings with the most matches are the most similar. It’s useful for doing a search where you’re OK with either slight misspellings or even minor words missing. The longer the string, the more trigrams and the more likely a match.

- SELECT show_trgm(‘Avatar’); – returns {" a"," av",“ar “,ata,ava,tar,vat}

-

PostgreSQL have more natural language processing capabilities (TSVector and TSQuery) and even can search by word phonetics (metaphone)

-

You could combine text search function in many interesting ways like the following query that “Get me names that sound the most like Robi n Williams, in order.”

- SELECT * FROM actors

WHERE metaphone(name,8) % metaphone(‘Robin Williams’,8)

ORDER BY levenshtein(lower(‘Robin Williams’), lower(name));

- SELECT * FROM actors

In this post we introduced PostgreSQL, a popular open source RDBMS. In future posts we will introduce more DBMSs.